By Munema Zahid

Behind a circular locked icon and a noticeably low follower count lies one of the only spaces 20-year-old Rameen has to herself: her alternate Instagram account, or her ‘finsta’. A university student and self-proclaimed feminist, her profile photo is an animated avatar, her username an obscure nickname, and all 19 of her followers handpicked to be trustworthy people. Beyond the lock, you’ll see an array of selfies, cat photos, and passionate rants.

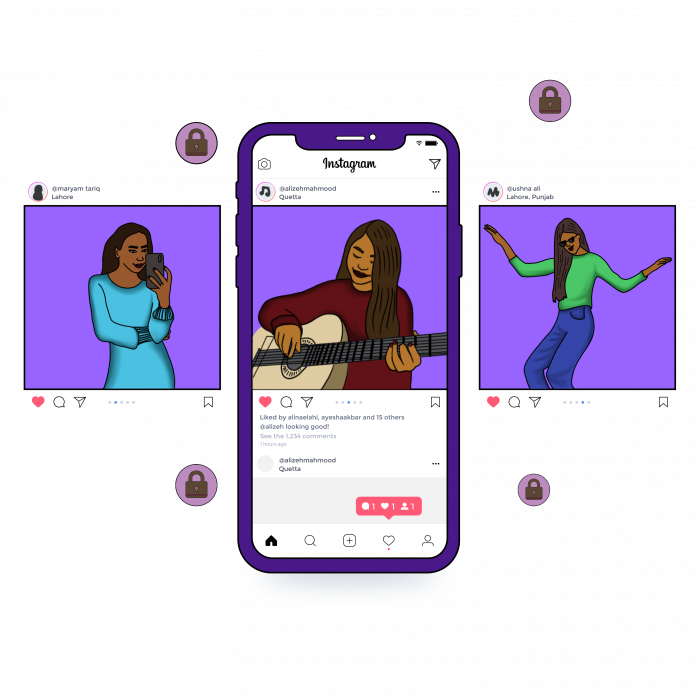

Finstas first became prominent in the digital landscape around 2017, seven years after the creation of Instagram and the rise of the perfectly-curated feed. Users realised the need for an outlet where they could post content that wasn’t exactly suited for their main account and the finsta filled that gap. A portmanteau of ‘fake’ and ‘Instagram’, the term is defined by The New York Times as an “intimate online space intended for an audience of friends, with the number of followers purposely kept in the low double digits”. But contrary to the name, a finsta can often provide a more authentic channel for self-expression, free from the scrutinising gaze of prying relatives and judgemental peers. And for women who already face heavy surveillance on their appearance, behaviour and physical mobility, the finsta can provide a digital safe haven.

The lack of gender equality in Pakistan manifests itself in multiple ways, one of which is the visible lack of women in public spaces. Roads are occupied by men, whether as pedestrians or loiterers, and out of all the vehicles present, only the occasional car will contain a woman—and rarely in the driver’s seat. Women are discouraged from learning practical life skills such as driving or fixing a car, usually told that the men in the house can do this for them, leaving them perpetually dependent. On the other hand, public transport options are poorly maintained and nearly unusable, while private options such as Uber or Careem are unaffordable for the average woman. Moreover, the level of comfort felt, either in a bus congested with men or alone in a car with a male driver, is another matter entirely. To keep themselves as safe as possible, women wrap themselves up in swathes of clothing (usually a large dupatta), walk briskly, and mind their own business, and this is when they’re permitted to leave home in the first place.

While Facebook remains the most popular social media platform in Pakistan by far, at over 46 million users, Instagram has seen the biggest surge in popularity. Its user base grew by 72% over the period from 2019-2021, compared to Facebook’s meagre 27%. However, it is yet to be ascertained whether this growth is due to new unique users, more secondary accounts, or both. Still, the app itself has implemented updates to make secondary accounts easier to create and manage. A recent update rolled out linked accounts, allowing users to create multiple accounts using the same login information, and quick account switching. With all these features, the app seems designed for people to create and utilise finstas, and young, technologically adept women are using this to their advantage in a patriarchal world.

Controlling appearances

Dressing as a Pakistani woman isn’t always a matter of wearing what you want. It involves balancing your family’s notions of respectability, your peers’ ideas of the current trends, and your own sense of self—a lifelong struggle that infuriates and exhausts. For some, each aspect of their physical appearance, including hair, makeup, clothing and general demeanour, is controlled and subject to judgement from parents or relatives. Lack of authority over her own appearance is one of many ways that a woman’s bodily autonomy and freedom of choice is stripped from her, usually by weaponising religion or parental authority.

For 20-year-old Areej, a university student, her physical appearance is an important way to express her identity. But her mobility is controlled by her parents, who are in charge of her transport to and from university, and are physically present with her mostly everywhere else she goes (such as family gatherings). Although Areej recently started volunteering online for Aurat March Multan, and her Instagram bio reads “perpetually angry feminist”, her parents do not hold the same views. “In the past, when mera jism meri marzi [my body, my choice] surfaced, my parents were very against it.” Areej’s multiple attempts to engage her parents in a productive discussion failed, leaving each of them to their own adamant views: “[My mother] said this is a dirty slogan and it goes against the values of Islam.”

When physical spaces were restricted and there was little room left for negotiation, Areej turned to the last option she had: social media. “Let’s say if I’m going somewhere with a guy, and my dad is dropping me, then I can’t wear a sleeveless shirt. But when I’m in my home, I can take my clothes off, take a picture, and post it on Instagram, and my parents cannot police that.” Although she is hindered from expressing herself openly in a physical space, her finsta offers a digital space where she can capture and memorialise her true sense of self. Areej emphasises, “It’s the only avenue I have to express my sexuality and just be who I am. I can be that woman I’m not allowed to be with my family.” Therefore, Internet access can act as a lifeline for women, providing them with a channel to express themselves in ways they can’t do anywhere else.

Controlling opinions

Although physical appearances and mobility can be heavily surveilled and restricted, the same isn’t true for one’s thoughts and beliefs. And often as a result of the restrictions they face at home, frustrated women branch out towards voicing their dissent and taking part in feminist resistance. Whether they assert their grievances at current events (such as the national femicide) or their own personal experiences, the outlet they choose for it is important. Women who dissent are subject to relentless judgement and attacks on their characters, from relatives or peers who take issue with these beliefs. When these women are already going through a never-ending struggle with the patriarchy in their daily lives, many don’t want it to follow them into their private safe spaces. “You can’t share your opinions openly without having to fight more than half the country’s population,” says Rameen.

For women who belong to other minority groups as well, they never know which parts of their identity can be safely revealed at any moment and which can’t. However, their finsta only has their trusted friends, who either already know about their identities, or wouldn’t judge them even if they just found out. Zoreen*, a 22-year-old university student who prefers to stay anonymous, says she often posts rants: “Mostly about my experience as a woman in Pakistan, or any experience that makes me feel angry or disrespected. Me being a Shia also goes there, as well as me coming from a strict family.” For Mins*, a 16-year-old queer girl who chose to speak under a nickname, her account holds whatever she feels like posting, and is the only space where she’s comfortable expressing her sexual identity.

Instead of exacerbating the struggles they have to go through, these women use their finstas as a place of comfort and respite, sharing their opinions with other like-minded people who they know and trust. Instead of tiring herself out with another fruitless argument with a sexist-minded person, Areej uses her Instagram to engage in productive discussions with other women. Fellow feminists and university students reach out to her by replying to her stories, and she says, “Instagram has not only allowed me to express my views and opinions, but it has also allowed me to build that circle with other feminists who I’ve learned so much from, and in whose company I’ve unlearned so much from as well.”

Both Areej and Rameen agree about having to portray a certain side of the feminist movement to people who don’t believe in it, to make it palatable and convincing. Therefore, their beliefs or decisions that would be considered much more ‘radical’, automatically retire to a more private space, to avoid tarnishing the movement as a whole. Rameen mentions, “I’m around a lot of people who think feminism is wrong. When I try to show them the good side, they react very radically even to that, so I have to keep a very mild opinion to avoid arguments. I have a lot of opinions that I can’t share, so I do that [on my finsta]. That way, you don’t get those holier-than-thou people in your DM’s.” Furthermore, Areej comments on how she attempted to convince her parents about the Aurat March slogan: “Mera jism meri marzi isn’t specifically about a woman wanting to go naked on the streets.” However, her true opinion differs: “I think that if a woman wants to use mera jism meri marzi to take her clothes off then that’s completely fine. I’m one of those women who does that.” Women campaigning for their own freedoms are also undergoing a balancing act, where they prepare the best, most convincing arguments for their family, and compromise on their more ‘provocative’ opinions. But in a carefully-guarded place where they don’t have to explain themselves or argue for their rights, they can let loose.

Dealing with the risk

These women treasure the safe space that they have on their finstas, which makes it even more important to keep them hidden away from the eyes of parents or relatives, forming yet another part of their ‘double lives’. They play two roles—one at home, a place of restrictions, and one when away from home, where they can be free. The rift between these two identities is carefully maintained to protect their safety and the few freedoms they already have, and since these women are savvier with technology than their families, they primarily use digital tools.

“I get requests from random aunties on my finsta, and I obviously don’t want them to know anything about me because they only know a certain side of me,” says Zainab, a 19-year-old university student. Her finsta isn’t easy to find even by searching her name, and she only follows other people’s finstas instead of their main accounts to ensure she isn’t identifiable on her friends’ followers lists. Additionally, Areej and Rameen have all their family members blocked, and Rameen keeps her finsta completely separate from her main account. Still, Zainab feels heavily anxious about any content getting out to her relatives or batchmates. She no longer posts on her finsta, but only uploads stories which disappear after 24 hours. In her ‘close friends’ list, she has only girls added, and chooses to upload certain photos there.

Although Zainab has never had any photos leaked so far (that she knows of), she recounts an incident in which she believed this was happening. Someone had set up an account for her, where the profile photo was one taken from her finsta.“I freaked that someone was leaking pictures from my finsta,” she adds. However, she later discovered that the account had been set up by her boyfriend, as a joke. Still, the paranoia follows her into almost every real-life situation. “Even if I move into the university hostel, and my parents come over one day to surprise me and I’m roaming over there in skimpy clothes, that’s literally my worst nightmare.” This feeling seems impossible to shake off, and both she and Rameen say that they cope by refusing to think about everything that could possibly go wrong. “Until it doesn’t happen, it shouldn’t take up space in my mind. If it happens, then we’ll do damage control,” Zainab adds.

On the other hand, a similar situation didn’t end that well for Areeba, a 23-year-old fresh graduate who prefers to stay anonymous. When she was in her final year at university, she had uploaded a photo of herself in a dress, on her finsta’s story. A few days later, a friend told her that a male classmate had screenshotted the photo, and had been sharing it with everyone in her batch. The friend who told her went on to blame her for uploading it in the first place. Areeba says, “Even now, people tell me that my photos are being spread in group chats or being shown around. One of my classmates had all my pictures saved.” From that day on until she graduated, she had to face stares and negative rumours at the university, and her classmates were overly lascivious when they approached her. Although after the second time this happened, she no longer cared about her classmates’ opinions, she was still worried about the news reaching her family, since her cousins studied in the same university. Areeba didn’t mind the invasion of her privacy, and decided to keep her head down and graduate as soon as possible, as long as she didn’t have to face the punishment her family would surely dole out.

For women who have had close encounters with nearly revealing their double lives, it’s easy to imagine the consequences if something compromising was divulged from their finstas. “Dire circumstances,” says Rameen, “The type we hear about on the news, something very extreme.” “I do feel like I might be sent to a religious camp,” Mins* confesses. Zainab has pictures with her boyfriend on her finsta, and she says, “If those get out, then I’m dead meat. They might kick me out of the house.”

Zoreen* has a benchmark with which to compare any potential repercussions. Once, she was showing a photo on her phone to her mother, who then began swiping through her phone gallery. She stumbled upon a photo where Zoreen* was standing with a male friend, with her elbow on his shoulder. As a result, she refused to talk to her for half an hour, before asking Zoreen* to open her phone and show her everything. “If she reacted like that to me just with my elbow on a guy’s shoulder, then there are a lot worse things for her on my finsta.”

Still, for many women, the benefits of having an unrestricted, unsurveilled space far outweigh the risks, even if the space is only virtual and accessed by a small handful of people. “Maybe I just feel reckless here, maybe there’s a very high chance I might get caught. But I’ve just gotten so much more reckless because I’m so, so tired of having lived this life,” says Areej. In a country where your life is dictated by the chadar aur char dewari (veil and four walls), and nearly everything around you infringes on your basic rights, you’ll eventually find an outlet to maintain and express your identity. For some young women, they can gain some of the freedoms they desire without ever leaving their homes.