By Areej Akhtar

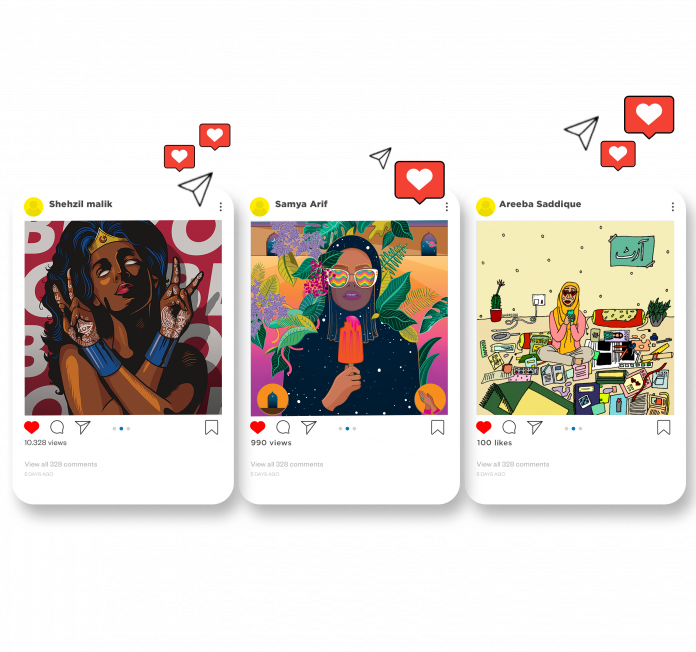

Credits: Top, left to right, Shehzil Malik, Maliha Abidi, Areeba Siddique

Bottom, left to right, Samya Arif and Sabika Abbas, Emil Hasnain, Isma Gul Hasan

Whether it is Shehzil Malik’s unabashedly fierce desi divas adorned with vibrant ornaments eyeing you as you scroll through your Instagram feed or Maliha Abidi’s traditional bride laden with gold, her kohl-rimmed eyes not beseeching you but screaming, “jahez-khori band karo,” creating a kaleidoscope of color and anger on your screen. Whether it is Emil Hasnain’s poster for Aurat March 2021 with five women, sitting cross-legged, serenely meditating against the backdrop of a uterus, hoping, hoping for their health issues to be taken seriously for once, or Isma Gul Hasan’s chthonic female navigating the “subterranean” that is her own mind. Whether it is Areeba Siddiqui’s hijab-clad women subtly shattering Eurocentric stereotypes about the hijab through funky renditions that reassert the hijabi’s agency, or whether it is the haunting, displaced eyes from Samya Arif and Sabika Abbas’ “Ghoorti Nazar” manifesting the omnipresent, ever-persistent “gaze” that dogs the female wherever she goes. Today Pakistani women have transformed Instagram into a digital haven, an online sanctuary of

expression and activism, a feminist art gallery where they exhibit not just the wonders they create, but also the woes that stimulate those wonders. While the lashing tongues of Pakistani misogynists leave no stone unturned in their efforts to disturb the peace of this virtual portal of feminist expression and empowerment, more and more women continue to seek refuge from the gripping talons of patriarchy in this dizzying yet liberating vortex of colors, illustrations, and icons that is digital art.

Modern-day Medusas: The Cyberspace as a Catachthonic Female Landscape

The widespread emergence of Pakistani feminist digital art on Instagram can be partially attributed to the proliferation of design technologies as innovative tools, gadgets, and software for drawing sketches, creating animations, and graphic designs are continuously introduced, renewed, or updated. For example, in 2019, Adobe Fresco, a vector and raster graphic editor was released by Adobe to facilitate digital painting and boasted of features like live brushes, layering, and the creation of scalable vector art. While the accessibility of these tools has enabled Pakistani women to explore digital art techniques in combination with or as an alternative to traditional mediums, one of the primary reasons why they have migrated to the digital space is because they are almost always denied conventional forms of expression. Like Medusa, wronged and banished from the face of the earth and relegated to the underworld, they too are exiled from physical spaces and are often left with nothing but the digital subterranean as the solitary space where they can exist and express themselves relatively safely.

Illustration by Isma Gul Hasan from her series “Landscapes of the Mind: Agency and Control”

Emil is a Lahore-based artist and illustrator. She is presently a senior at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and runs an art account on Instagram with the username “padpixie” and enjoys a staggering 3265 followers. Among other things, Emil has designed the official poster for Climate Impact Pakistan’s Smog Action Rally, the front cover for the LUMS School of Education Digest, the front cover for the Annual Report of the Humanities School at LUMS for the year 2020-2021, and an illustration for Usman T. Malik’s book “Midnight Doorways: Fables from Pakistan.” Emil also designed a poster for Aurat March 2021, the theme for which was “Womxn’s Health.” Speaking about the poster, Emil says, “I always wanted to go to the March but my parents are very against it, so I wanted to contribute to it somehow, and I wanted to do it as discreetly as possible. I really wanted to make a uterus but I also wanted to stay as lowkey as possible, I did not want it to be immediately visible which is why I included the women doing yoga right in front of it, in case my family traced the poster back to me. On Instagram, there is certainly some anonymity because I can choose how much personal information I want to reveal. For instance, I avoid disclosing my last name, for safety reasons and also because I don’t want to be remembered as someone’s daughter, but as myself and for my own work. ”For a lot of female digital artists then, cyberspace becomes a catachthonic realm, and they themselves modern-day Medusas, not defeated but powerful in their rage that they can manifest, unperturbed by patriarchal forces to some degree.

Poster for Aurat March 2021 “Womxn’s Health” designed by Emil

Reconceptualizing Pakistani Women: Deconstructing Stereotypical Representations

In both local and international media, Pakistani women, especially Muslim women, are viewed and consequently represented with a myopic lens, and the portrayals often pander to the age-old tropes of the “oppressed woman in need of saving,” “angel in the house,” or “the fallen woman,” completely dismissing the diversity of female experiences and realities in the country. However, many Pakistani digital artists who run art accounts on Instagram are shattering these narrow stereotypes and depicting Pakistani women in a way that is more faithful to their lived reality, untainted by the fetishization that both regional patriarchal forces and Western feminism subject it to.

Portraits of Pakistani women illustrated by Maliha Abidi for her book, “Pakistan for Women: Stories of women who achieved something extraordinary”

Maliha Abidi is a Pakistani-American artist and author whose work has been featured on the BBC, The New York Times, The Guardian, and The Malala Fund among other prestigious publications. Her debut book, “Pakistan for Women: Stories of women who have achieved something extraordinary” was launched in 2019 and catapults to the forefront stories of 50 Pakistani women along with their illustrations. The arresting portraits that Maliha has illustrated pay homage to the resilience and strength of Pakistani women and demonstrate that Pakistani women are not merely passive recipients of patriarchal abuse who need to be “saved” but active combatants who refuse to perform a kowtow to sexist social norms. For instance, Maliha’s book includes a portrait of Veeru Kohli, a Pakistani Hindu woman who was a bonded labor activist

and launched a campaign against its practice in 2013. However, because Veeru’s story is a story that stems from the margins, it has almost been washed away by the unforgiving waves of time, and Maliha’s portrait, which depicts Veeru in all her feminine glory, clad in a red saree sporting large bangles on both wrists and a confident smirk, preserves her occluded history. Speaking

about the power of digital art in reconceptualizing portrayals of Pakistani women, Maliha tells me, “I feel like the thing with digital media is that whatever you present, it will always stay there, and when it comes to women, in Pakistan, the diverse experiences of women belonging to ethnic and religious minorities are never explored; only a singular representation of the Pakistani woman is seen in the media. If you were to Google Pakistani Hindu or black female activists, a lot of names will come up, but a lot of people don’t know about them. I think online we can preserve and celebrate the diverse stories of these women better for future generations. People will see these portraits and think, “Here is an account of a woman from Pakistan,” and it is very different from what you see in most media.”

Portrait of Pakistani Hindu bonded labor activist Veeru Kohli illustrated by Maliha Abidi

Shehzil Malik is a designer and illustrator from Pakistan whose work has been featured in CNN, DW, BBC, and Forbes with clients including Sony Music, Penguin Random House, Oxfam, New York Times, GIZ, and Google. She is a Fulbright scholar with an MFA in Visual Communication Design from the Rochester Institute of Technology and is part of the International Development Innovation Network (IDIN). Her dynamic representations of Pakistani women merge different aspects of their national, ethnic, and religious identities as well as the Western influences they have adopted, and in doing so, shatter the hegemonic depictions of Pakistani women which have careened through local and international media over time. For instance, in the West, the hijab has usually been seen as a tool of patriarchal oppression and a symbol of Islamic extremism, and the hashtag “#HandsOffMyHijab” has gained much traction

online after the French government passed an amendment on April 8th, 2021, banning the hijab being worn for girls under 18. However, this illustration by Shehzil (see below) which depicts a woman with the traditional Islamic hijab who has also donned a shirt with the words “GIRRRL POWER” on it and a Western leather jacket, her eyebrows raised in daring smugness, demonstrates the diverse experiences of hijab-wearing woman and tears down the Eurocentric assumption that every woman who wears a hijab is in need of feminist enlightenment and empowerment. During an interview with Naila Tasnim, Shehzil said, “When I am drawing hijabis, I do it very deliberately, and when I am not drawing them, that is also very deliberate. I started drawing because I could not find anything that looks like me, anything that is kind of close to what I was thinking, or what my friends were thinking, like I’m not even just talking about Netflix, or Hollywood, like do I see myself reflected there? Obviously not, but even within Pakistani media, where is, whatever you call a modern Muslim female voice?”

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

Areeba Siddique is another Karachi-based digital artist, with a massive following of 75.8k people on her Instagram art account with the username “ohareeba,” and through her illustrations, she too challenges misconceptions about the hijab and portrays hijabi women in a way that highlights their agency and autonomy over their bodies. The following illustration shows multiple women, each having styled the hijab in a different fashion; one of them wears a cap on top of it, one has styled it with a bandanna, one wears a Nike headscarf, while one a burqa, and all of them are sporting jewelry and sunglasses. These details emphasize the different ways through which hijabis explore and incorporate modern fashion trends in their everyday attire and thus negates the idea that they have little or no choice in matters of the body because they have been “confined” by the hijab or the veil. Clearly, digital art on Instagram has become a platform for redrawing the image of the Pakistani woman which has undergone vicious distortions through local reductionist lenses and fetishized Western lenses.

Illustration by Areeba Siddique

The Fluidity of Art: Merging Traditional and Digital Mediums

Many of these artists have not abandoned traditional forms of art, instead, they use them to complement the creation of their digital art, blurring the lines between these strictly-segregated domains and challenging not just conventional notions of gender, but also art. Maliha, who has created the portraits for both her books using traditional art supplies and tools, and also digitally showcased them on Instagram, says, “I still produce art pieces that are produced using paints, or color pencils, or ink. When I am traveling, it is easier to carry my tablet so creating digital art is more convenient. So I work with both mediums.”

Portraits of Pakistani women illustrated by Maliha Abdi for her book, “Pakistan for Women: Stories of women who achieved something extraordinary”

Similarly, while Emil also initially began exploring art through traditional mediums and only started dabbling in digital art in 2019, she too does not make a strong distinction between the two processes anymore. She tells me, “Even right now, the art that I create digitally is inspired largely by the sketches I had drawn or other pieces I had created using traditional mediums previously. Even now people see fine art and digital art as two separate fields and many do not even consider digital art ‘real’ art. But, I took this course at LUMS, and we read Dante’s Inferno for it, and the professor gave us a task to write our own Inferno. I asked if I could draw it, and I did, and much of it was inspired by Hieronymus Bosch triptych The Garden of Earthy Delights. He is an artist that I really, really look up to, and he used to make traditional oil paintings, so many of my illustrations are inspired by his style. And I think it’s a little unfair when we segregate these two processes too much and say, okay, this is fine art, and this is digital art, so I prefer using the term mixed media now.”

Illustration by Emil Hasnain for Usman T. Malik’s book “Midnight Doorways: Fables from Pakistan”

Isma Gul Hasan is a Karachi-based illustrator who received her Bachelor’s degree in Visual Communication Design from Beaconhouse National University and completed an MA in Illustration from Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London. Isma has designed posters for Aurat March Islamabad and worked as an illustrator at Shehri Pakistan. She also believes that the boundaries between digital and fine art are increasingly being dissolved. “It wasn’t a very linear journey, from traditional to digital. I’ve been drawing since as far back as I can remember, and obviously, I started with basic pencil drawing. Thinking digitally came when I started my degree in Visual Communication and Design. That is when I was exposed to

software and working with a tablet, and what illustration means, and since then, I have been oscillating back and forth between traditional and digital, sometimes working entirely digitally, sometimes working entirely traditionally, and my work now is basically a mixture of both,” she tells me.

Reimagining and Reclaiming the Feminine

For women, art, be it traditional or digital, is more than a creative pursuit; it is also curative since it has the potential to heal the wounds inflicted by a devouring patriarchal society. Isma’s Master’s project, “Landscapes of the Mind: Agency and Control,” a series in five parts, shows how digital art allows women to reclaim the agency and autonomy that they have been stripped bare of. Speaking of this project, Isma says, “It takes snippets from a woman’s journey who is trying to reclaim her sense of self and reconnect with a part of herself which lay buried as a result of trauma, as a result of the harsh reality that she lives in. These landscapes are inner landscapes that are influenced by her outer reality, which is very harsh, very violent, very oppressive, and how that preys upon her mind, how her mind and the inner space which is supposed to be the innermost, private space that she has, is no longer her own and has been shaped violently by things that take place externally in her life. There is this monolith that features in the illustration, and that’s a physical manifestation of patriarchal control, it has completely invaded her mind and changed that landscape, and it has obscured the otherwise serene sky that she used to know in her mind, making her wander in these landscapes in an attempt to stitch together a sense of self. The white egg-like shapes signify her coming towards healing, towards a deeper truth about herself.”

Illustrations by Isma Gul Hasan from her series “Landscapes of the Mind: Agency and Control”

Isma’s project, like artwork by other female digital artists, is a testament to the ability of art to serve as an outlet for feminist exasperation and facilitate the healing of the female in the process. As more and more Pakistani women venture into the digital art realm, we witness the curation of a brown feminist e-gallery on Instagram where women redefine not just themselves but also what it means to be a digital artist. Author’s Biography: Areej Akhtar is a student at the Lahore University of Management (LUMS), where she also serves as the Content Head for the Publications Society at LUMS. She plans on majoring in English Literature and is currently working as a Journalism Intern at Blue Blood International. Much of Areej’s writing focuses on the experiences and lives of women. Some of her work can be read here and here.